Legal Status

- Wildlife Act 1976 / 2000

- Bern Convention Appendix III

Key Identification Features

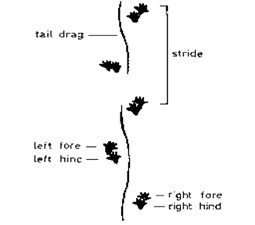

The pygmy shrew is Ireland’s smallest mammal measuring only between 4.5 and 6 cm with a long slender tail reaching up to 5 cm in length, fully grown adults will weigh less than 4 grams. Body colouration is of a darkish brown tint with a lighter underbelly with the tail being more sparsely covered in fur. They will moult their coats in the early summer before growing a thick coat again for the colder winter season. The pygmy shrew is often mistaken for a mouse as it also has long whiskers, short ears and small eyes, however the main distinguishing features are the shrew’s more velvet like fur, smaller body size and a lightly furred tail. The head tapers into a long flexible snout which it uses to sniff out its prey as its eyesight and hearing are poor. Movement can be described as a scuttling type run in short speedy bursts. They are a vocal species emitting very high pitched chattering sounds while hunting and short hissing noises if alarmed or threatened. Due to the small size of the shrew, tracks will appear as light impressions on soft sandy soil with the hind foot measuring only up to 1.2cm in length. They can swim well and are good climbers but will spend most of their time foraging at ground level. The pygmy shrew was thought to be Ireland’s only shrew species until the discovery of greater white-toothed shrews in Tipperary and Limerick in 2007. The greater white-toothed shrew has a more grey or reddish brown colouration on the sides and back which turns to a more yellowish colour on the undersides. The tail is covered in long whisker like white hairs but the main distinguishing feature is the differences in the shrew’s teeth with the greater white-toothed shrew containing an outer row of white teeth. Greater white-toothed shrews are slightly larger and heavier than the pygmy shrews with adults reaching up to 9 cm head and body length and weigh up to 10 grams when fully grown.

Habitat

Pygmy shrews are found throughout Ireland in a variety of habitats ranging from areas bordering coniferous and deciduous woodland to any area with good ground cover such as grasslands, heaths, hedgerows, peatlands and sand dunes. They are largely absent from heavily forested areas. The pygmy shrew requires dense vegetation for cover from its many predators and to provide adequate foraging areas for insects. They generally remain above ground and build circular nests of dried grass concealed in long vegetation or under rocks and logs, they will use a series of regular pathways which appear as tunnels within the ground vegetation for movement between the nest and foraging areas, if available they may sometimes use the abandoned underground tunnels of other small animals. An individual pygmy shrew’s home range will be quite small in size especially if it is occupying the preferred habitat type of open grassland areas which supply good cover and foraging sites, such ranges generally measure from 200 m2 up to 1,500 m2. The habitat requirements of the greater white-toothed shrew are similar to those of the pygmy shrew with greater white-toothed shrews perhaps preferring more coastal areas and are often found near rural outbuildings so they may have a closer association with human settlement.

Food and Feeding Habits

Pygmy shrews are un fussy opportunistic hunters who primarily feed on insects which inhabit leaf litter such as beetles, spiders, woodlice, insect larvae and bugs. They have a high metabolic rate so are required to hunt and feed every few hours meaning they must be active both night and day throughout the entire year, they must consume their own body weight in food every day to survive as they are so small they will burn most of their energy while hunting and are unable to store excess energy as fatty tissue. Because of their high metabolic rate a pygmy shrew will starve to death within four hours if it is unable to feed. The use of refection to gain all available nutrients from their food is regularly practiced. They are skilled hunters and will patrol their home ranges every three to four hours along regularly used pathways within vegetation, if they leave these pathways they become more hesitant and must feel their way along using their long whiskers guided by their keen sense of smell as their vision and hearing senses are so poor. In Ireland beetles and files constitute about half of the pygmy shrew’s daily diet. The greater white-toothed shrews will have a similar diet to that of the native pygmy shrew although they have been known to hunt lizards and smaller rodents in European countries where they are already established.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Pygmy shrews are usually very territorial in nature but this becomes more relaxed during the mating season when males will travel through other shrew’s home ranges in search of breeding females. This shrew species breed from April to October with a peak in mating activity occurring in the month June. Females give birth to an average of six young per litter with two litters per year being the norm. The gestation period for the young is only 25 days after mating, with baby pygmy shrews weighing only 0.25 grams at birth. When born they are furless and rely on their mother for food and warmth, breeding females have the ability to become pregnant with a second litter while the first is still being weaned. Parental care of the young is given by the female only. Within two weeks of birth the young shrew’s can have gained ten times their original body weight. Weaning generally lasts for three weeks with the young becoming fully independent and established within their own territories by the age of one month. The mortality rate for newborn shrews is high especially if their fist winter is a harsh one, those that survive will breed the following year before dying in their second winter meaning that the average life span of a pygmy shrew in Ireland is only 14 months. The greater white-toothed shrew species have a higher reproductive rate than native pygmy shrews with up to five litters being produced each year with each litter containing between two and ten young. The female greater white toothed shrew is less aggressive during the breeding season and sometimes allows the male to remain in the nest with the young while she leaves to forage so both male and female will show their offspring parental concern. If a nest is disturbed the mother will lead her offspring to a new site by caravanning which is when each shrew grasps the tail of the shrew in front forming a chain which is a behavior not associated with the pygmy shrew species.

Current Distribution

The pygmy shrew species has been present on the European continent for 2 million years and are now widespread throughout northern Europe and extend to the Artic coast of eastern Russia, they are absent from Iceland, southern Spain and the middle east. They are thought to have arrived in Ireland from Britain after the last Ice Age, the pygmy shrew is now found throughout Ireland and on some offshore islands wherever habitats that support a large insect population are to be found. As they can tolerate elevated and damp conditions there are few places where a pygmy shrew will not set up residence except in dense forests and on regularly mowed grounds. Population densities may range from five to forty individuals per hectare depending on the suitability of the habitat and the time of the year with the population reaching its height in summer before dropping dramatically in winter as the previous year’s newborns die off. The recently discovered greater white-toothed shrew is one of Europe and Asia’s commonest shrew species. They currently range across Europe, North Africa, Britain and some Mediterranean islands. They are believed to have been introduced by man to all areas outside of their traditional range in Eurasia.

Conservation Issues

Due to their small size and large numbers the pygmy shrew is a favorite prey species for a number of other animals and birds in Ireland including foxes, pine martens, stoats and predatory birds like owls, hawks and eagles therefore they are an important link in Irish ecosystems. Due to their small size they are extremely sensitive to any adverse changes in the environment for example an increased use of pesticides and herbicides in some rural habitats may directly kill pygmy shrews or reduce the supply of insects on which they are totally dependent. The increase in the population of domestic and feral cats in Ireland could be having an adverse effect on pygmy shrew numbers here especially in more rural locations. The importance of the pygmy shrew to the proper functioning of the Irish ecosystem has now been recognized as it is a protected species under national law and international convention. The discovery of the new greater white-toothed shrew species may have a considerable future impact on local Irish ecology. They are likely to be beneficial to predatory birds in Ireland in particular the barn owl and kestrel but they may threaten already established rodents here such as the pygmy shrew and the bank vole as they will compete for similar habitats and food items. The greater white toothed shrew population is likely to increase as they will expand their Irish range over time so they have the potential to replace the native pygmy shrew in some areas due mainly to their greater reproductive capacity.